Minneapolis: Peace in Practice

Photo by Jeff Schad.

Our true values are not the ideals swirling in our heads. They are only these: our actions.

In a teetering democracy, injustice quickly fills the void created when we fail to live our values.

The value of peace is neither silent nor passive; it requires relentless tending.

Last week, I wrote about Minnesotans embodying peace. Now I want to chronicle some specific acts my family, friends, and neighbors are undertaking in my hometown of Minneapolis. They are showing us the path forward. We can’t look away.

Speaking truth to power

Thousands of peaceful protestors are packing the streets, demanding peace, justice, and accountability. They are, quite literally, singing their resistance across the city. Residents are calling and writing to their elected officials, articulating their expectations for meaningful action. My lawyer friends are involved in suing the heck out of the federal government to ensure it upholds that pesky little foundational document: our Constitution.

Caring for community

Residents are attending trainings to better understand our Constitutional rights. They are calculating the risks they are willing to take to keep our democracy afloat. They are alerting each other to the presence of federal agents.

They are checking on friends, colleagues, and neighbors with targets on their backs. In Minneapolis today, that means pretty much everyone who is not stark white. As ICE picks off people, regardless of legal status, from parking lots, gas pumps, and places of work, and ships them immediately to Texas detainment facilities, many families are left hiding fearfully in their homes. Community members are taking up food collections, delivering supplies, driving their kids to and from school.

Some have even created networks to hide families in their houses—a modern-day Underground Railroad. Yes, this is where we are right now.

Residents have also formed a group to escort those being released from the horrors of wrongful detainment in the middle of the night, in subzero weather, sometimes without a phone, coat, or even shoes. They are comforting them, providing them with meals and clothing, taking them to safety, reminding them that, despite the cruelty they just endured, compassion still exists.

Bearing witness

As a lifelong documentarian, I’ve always believed that bearing witness to another’s life is one of the greatest gifts we can offer. Minnesotans are planting their feet firmly on the ground and observing others’ experiences, despite serious personal risk. They are filming violent actions. They are providing official testimonies. They are attending candlelight vigils and memorial bike rides for those murdered by federal agents. Their presence sends a clear message to fellow community members: We see you. It also sends a clear message to the forces occupying the city: We see you.

Sharing their stories

Minnesotans are not only bearing witness but zeolously sharing what they’re seeing with the rest of us every time they upload a video, give an interview, write an article, or post about their experiences on social media.

They also orchestrated a chilling SOS photo, taken on a frozen lake with the Minneapolis skyline as a backdrop (shared here). The world took note.

(I was unsurprised to learn that numerous childhood friends participated in the SOS photo. That lake, Bde Maka Ska, is the epicenter of outdoor living in the city. Growing up, we walked, ran, biked, and rollerbladed around it regularly. We skated on it in the winter. We paddled across it in summer. I never make a trip home without visiting it. Just last summer, we canoed around it with my very first friend in the world and her family.)

Engaging in small acts with big potential

People are knitting and crocheting red “Melt the Ice” hats, a nod to those worn by Norwegian resistors during WWII. (My daughter is making me one!) I hear it’s become difficult to find red yarn in Minneapolis. While things like hats may seem silly or even frivolous, they are anything but. I call wearing such an item an “everyday mention,” a casual, nonconfrontational way to signal your position. Research shows that a key trigger for cultural change comes from prevalence signals, meaning clues that convince a person they are not alone in their values, that others agree with their stance. This realization is how momentum begins to build. A hat is never just a hat.

Finding joy in resistance

A family member decided that one of his acts of peaceful resistance is to go around the city and eat as many delicious tacos as humanly possible from immigrant-owned restaurants.

I’d never considered the importance of delighting in resistance until last summer, when I attended a book talk by activist Loretta Ross. She pointed out that our work will not be sustainable unless we find joy in it. And since peace can never be left unattended, we’ve got to find ways to keep ourselves going for the long haul. In other words, it’s imperative to find your tacos!

I’ve always said that Minnesotans are the hardiest people you’ll ever meet. We’d never let a bit of ice keep us from living our values.

What Does Peace Look Like?

My two worlds collided this week.

On Thursday, I woke up at 5:30 a.m. and drove 30 miles into the country. I parked my car in the dark, along a side street in a rural North Carolina town. I waited.

Forty-five minutes later, the first flashing lights of the escort vehicles appeared. A few minutes after that, the monks emerged, walking down the street at a fast clip toward me.

It was Day 89 of their 120-day, 2,300-mile Walk for Peace from Texas to Washington, DC.

By this point, the street was dotted with onlookers, and traffic had stopped in both directions.

I thought it would be kind of neat to see the monks. I didn’t expect just how moving, how palpable the experience would be. But as they passed within a couple feet of me, the rest of the world fell away; I could only feel their energy. Somehow, in the dim morning light, they seemed to be glowing in their orange robes. They were truly emanating the peace and joy they sought to share.

As I bowed my head in reverence, I brought my hands together and found myself clasping them around the necklace my mom had just given me for Christmas: a Lake Superior agate cut into the shape of my beloved Minnesota.

My legs shook, and a single phrase looped through my mind as, one by one, the monks filed past:

Peace be with you, Minnesota.

The next day, as the monks continued their journey through North Carolina, welcomed by throngs of people hungry for their peace message, tens of thousands of Minnesotans staged an “ICE Out” march in -20-degree weather. Shuttering businesses and schools, they took to the streets of Minneapolis in peaceful protest of the federal occupation. Among them, around 100 clergy were arrested at the airport, where they were asking airlines to stop providing deportation flights.

I’ve always adored my hometown, but I’ve never been prouder of it—of the way the community has come together in defense and diligent care of their neighbors, in their relentless rejection of injustice, in their steadfast demand for peace.

Just one day later, outside my young niece and nephew’s favorite donut shop, federal agents executed a peaceful observer, who was a U.S. citizen and ICU nurse at the VA hospital. (Those details don’t actually matter to me. Only this one: He was a person.)

Neither a profound encounter with the venerable Buddhist monks nor spending the last year and a half studying how my Quaker abolitionist ancestors lived their peace testimony through our country’s foundational struggles could prepare my heart for such an event.

Today, I’ll admit I’m feeling anything but peace as I grieve this death and its significance for my hometown, for our country. But I also know that *living* the value of peace is our path toward something better.

What I’ve learned from my ancestors’ legacy is this:

Peace is not just a noun; it is a verb, it is action.

Peace is not silent in the face of injustice; it is unyielding.

Peace does not involve shying away from discomfort or conflict, but walking toward it with compassion, integrity, and hope.

Peace does not excuse us from individual or collective action just because systems are broken and in desperate need of repair.

Peace requires us to speak truth to power (a Quaker phrase, no less).

What does peace look like in practice? It looks a whole lot like the monks traipsing across the country and the thoughtful, selfless acts of my family and friends in Minnesota.

Peace be with you, Minnesota, and with the rest of us, too.

Book Cover: Information Crisis

After years of research, interviews, writing, and editing, I’m pleased to share that Information Crisis: How a Better Understanding of Science Can Help Us Face the Greatest Problems of Our Time has moved into production and will be published in April 2024. You can read the book description here.

Now come the fun parts, starting with the cover reveal. Ta da!

Pithy sayings aside, readers do judge a book by its cover, which makes the cover a critical piece of the marketing package. Typically, a publisher hires a graphic designer to create a book cover, and the author may or may not have any input on the design.

My process is different from traditional publishers’. I’ve always created my own book covers, with my photography serving as a primary design element.

My graphic design experience harkens back to elementary school, when I first opened a business designing stationery using Print Shop software, which I sold to my family at exorbitant prices. I’ve since designed all manner of wedding invitations, birth announcements, and holiday cards for clients. For me, graphic design is a calming escape from writing that exercises my creativity in an entirely different way.

Designing my own book covers gives me the opportunity to help shape a potential reader’s first impression. After pouring years of work into a book, it feels like a weighty but worthwhile task.

Conceptualizing a cover for Information Crisis was challenging, because the book explores such a large range of subjects. I didn’t want to limit readers’ initial perceptions by choosing a cover that emphasized just one of the many themes the book addresses, nor did I want a cover so abstract that it might not make a clear connection to any of them.

Instead, I decided to pull from two separate anecdotes in the book to create the central image.

In one of these narratives, I use my family’s love of searching for fossil shark teeth on Topsail Island, NC, to illustrate how our brains use shortcuts to simplify incoming information. For example: black + shiny + triangular = shark tooth. These shortcuts are crucial for making snap decisions, but they can also skew our perceptions of the world by conjuring patterns that don’t exist, like turning a blackened piece of driftwood into a Great White tooth. The book traces how a variety of players across society commonly prey on our numerous brain processing shortcuts to distort our understanding of scientific information for their own gain—and how we can protect ourselves.

In the second narrative, which comes toward the end of the book, I introduce the joy and value of participating in citizen science by documenting my own adventure on a shark-tagging trip in Miami’s Biscayne Bay.

To make the cover image, I asked my daughter, Cricket, to draw an outline of a hammerhead shark. It was meaningful that Cricket participated in the cover creation, because, as you’ll soon read, she stars in the book as a tiny research subject in a years-long clinical trial.

I placed fossil shark teeth my family and I had collected over the years into Cricket’s shark outline. Those little teeth were slippery, and I kept knocking them out of position. My frustration could be heard throughout the land. Once I had finally placed all the teeth, I photographed the image.

Different colors are associated with different book genres and themes. For instance, books about the environment often incorporate greens and blues, while books about health often use reds. Again, I didn’t want to select a background color that might suggest narrow subject content. So I chose a bright yellow-orange to signify urgency and the need for attention, like a traffic sign or a double-yellow line.

Even selecting the right shade of yellow-orange was a process that required numerous drafts and printings. Earlier digitally generated versions of the background felt too dark or too bold, which seemed to distract from the shark. Eventually I brought out the watercolors and physically painted a background on textured paper, then scanned the painting. This technique softened the background, which I hope will help to draw the reader’s eye to the shark.

Time will tell if these calculations will result in attracting the intended audience of bright, curious readers!

A Spooky Story for a Spooky Time

Gather ‘round. Let me tell you a story. It may feel familiar, but keep reading to the end. You’ll surely be surprised.

Gather ‘round. Let me tell you a story. It may feel familiar, but keep reading to the end. You’ll surely be surprised.

There once was a nation embroiled in politics. In the thick of their political passions, a virus emerged. It struck the people of this nation in waves, the first one smaller. The president ignored the virus, as did many local politicians. Much of the media ignored it at first too, not wanting to hurt morale or detract from the president’s ambitions.

Doctors tried to warn the public to distance from each other, to wear masks. But voices with other agendas drowned them out. The media parroted these voices, and the people parroted the media.

I refuse to live in fear. Fear is the real enemy.

It’s just the regular old flu.

There is no reason to be alarmed.

Our enemy across the ocean purposely spread this illness to us.

Soon a pattern developed around the country: Downplay, distract, die.

Fringe doctors and con men began to loudly tout untested, sure-fire, silver-bullet prophylactics and cures for the disease, and ads popped up everywhere peddling such remedies.

Quinine.

Disinfectant injections.

Common over-the-counter medications and supplements.

Downplay, distract, die.

Meanwhile, the second wave rampaged the country. It took many, many more lives than the first.

Some cities tried to shut down shops and restaurants to prevent the spread of disease, but it only really helped in places where people fully embraced the idea that they needed to isolate from each other.

Scientific studies began to circulate before they were peer reviewed, meaning they were far from complete. There just wasn’t time to wait around. But many of these studies were poorly conceived, poorly executed, and poorly analyzed. Some were downright fraudulent. They should never have seen the light of day.

Many homeopaths claimed 100 percent cure rates from their herbal remedies, stealthily removing all the dead patients from their rosters.

Downplay, distract, die.

The country’s official death count from the virus was 675,000. Globally, many millions more died. These statistics are likely vast underestimates of the total mortality.

Now here’s the astonishing twist: this is not the story of the Covid-19 pandemic. It may as well be, but it’s actually a book report on John M. Barry’s The Great Influenza, which chronicles the 1918 influenza pandemic.

Scientific innovation has progressed to the point that we now have the ability to end the Covid-19 pandemic using highly effective vaccines coupled with basic public health measures. But over the last century, much of the public has not progressed in their understanding of how science works, what it offers us, and what it is not, resulting in an extreme vulnerability to misinformation. And so, even though it no longer has to, the same pattern continues to ring in our ears today:

Downplay, distract, die.

My 2020 writing round-up

Happy New Year! Every January, I try to pull together a round-up of projects I accomplished over the last year and set goals for the following. But here we are at the end of January, and I’m still processing all the peaks and valleys of 2020. One thing I learned last year was not to set personal or professional goals during a pandemic, aside from survival. So this list will mostly focus on the things that did happen in 2020 rather than lay out goals that probably won’t happen in 2021.

I wrote a book! Equus Rising: How the Horse Shaped U.S. History (illustrated by Montana artist Robert Spannring) hit the shelves in May 2020. I’m going to admit it: I’m really proud of this book. It’s not a bestseller. The monetary reward has not exactly been impressive. But the responses I’ve received from strangers, friends, and family all over the country have blown me away. Knowing that people have spent some of their precious time reading my work is extremely humbling. Knowing that they have enjoyed it and learned from it is, to a writer, an unfathomable privilege. I’ll never stop saying this: we cannot make progress as a country if we ignore the realities of our past. I hope Equus Rising adds to your knowledge of our history.

I (accidentally secretly) launched a publishing company called Hill Press. It wasn’t meant to be a secret, but, as you’re well aware, the year didn’t go quite as planned. As for many of you, family obligations largely relegated my professional life to the back burner as 2020 progressed. Hill Press doesn’t even have a shingle up on the internet yet (besides our new Instagram account), but we’ll get there. I look forward to sharing more with you about the company and our mission in a more official way this year. In the meantime, here’s a hint about where we’re headed: we’ll focus on identifying new voices and publishing perspective-shifting work.

Hill Press published our first short story collection, Stray Dogs and Saviors: Stories, by Erin Connors, in December 2020. You can learn more about Erin’s fantastic debut collection here.

I wrote several shorter pieces throughout the year. Here are a few of my favorites from around the web:

Most of us won’t die from COVID-19. But looking beyond the basic statistics can help us to better assess and mitigate the virus’ risk to our personal health.

We’ve been having the wrong conversation about abortion. Let’s change it.

Our country has long excluded people of color from accessing the power of the horse

Becoming a more responsible consumer of health and science news in the age of COVID-19

I also became a volunteer for an incredible nonprofit, CORRAL Riding Academy, over the summer and started contributing to their blog. Here are a few of my favorite posts for CORRAL:

Teaching the process of resilience

The adultification of Black girls

Health disparities illustrate the heavy burden of structural racism

Thank you for all your support of my creative endeavors this year. Your readership and encouragement make it all worthwhile. As you gear up for the uncertainty of Pandemic Year 2, I encourage you to set low expectations and celebrate small successes as if they were major victories—because if we’ve learned anything in the last year, it’s that in a pandemic, small success are major victories.

Hill Press publishes first short story collection, “Stray Dogs and Saviors,” by Erin Connors

I’ve got two exciting pieces of news to share with you to kick off 2021. The first is that last year, I launched a small publishing company called Hill Press. It wasn’t meant to be a secret, but, as you’re well aware, the year didn’t go quite as planned. As for many of you, family obligations largely relegated my professional life to the back burner as 2020 progressed.

Hill Press doesn’t even have a shingle up on the internet yet (besides our new Instagram account), but we’ll get there. I look forward to sharing more with you about the company and our mission in a more official way this year. In the meantime, here’s a hint about where we’re headed: we’ll focus on identifying new voices and publishing perspective-shifting work.

The second news item is that, despite our quiet launch, Hill Press published our first short story collection at the end of 2020, Stray Dogs and Saviors: Stories, by Erin Connors. Not only is it our first foray into the world of short stories, it’s also the author’s debut collection. I can’t wait for you to read her bright, humorous, thought-provoking book. After you’ve spent time soaking up Erin’s unique and delightful writing, you’ll be glad to know she has a nonfiction book in the works, too.

Stray Dogs and Saviors book description: From the local schoolyard to the business districts of Singapore, from a pine forest to a luxury resort in India, the characters in these stories confront the reality that dreams don’t always come true. Power imbalances and gender expectations hem them in, and slow and steady doesn’t always win the race. Yet, as they move between the mundanities of their lives and their fantasies, they sometimes encounter the satisfactions that lie somewhere in between.

Erin Connors is a writer and educator whose work has appeared in various publications, including the Asheville Citizen-Times and the Journal for Understanding and Dismantling Privilege. Though she is not critically acclaimed, she did once win second place in a Lonely Planet travel writing contest. Then she had a family, with whom she now lives in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, where she rides her bike and blogs at writingforchocolate.com. This is her first short story collection.

Stray Dogs and Saviors: Stories is available for purchase here.

Please write a review on GoodReads and/or Amazon! Book reviews are essential. They help make books more visible to future readers.

Most of us won’t die from COVID-19. But looking beyond the basic statistics can help us to better assess and mitigate the virus’ risks to our personal health.

Image by kjpargeter.

We are constantly bombarded with the basic numbers of COVID-19: deaths, hospitalizations, and cases. These statistics are crucial to evaluating the virus’ spread, but they provide an incomplete picture of the numerous ways COVID-19 can influence our health even when our personal risk of mortality from an acute infection is low. Moving past these surface-level numbers and examining some of COVID-19’s broader health implications can help to inform our own risk assessments and behavior choices as we navigate daily life in the months to come.

We can’t just look at COVID-19 mortalities. We have to look at morbidities too—that is, the long-term consequences of the virus. Although researchers are just beginning to untangle COVID-19 morbidities, they loosely fall into two potentially overlapping camps. The first camp is COVID-19 cases that linger. While it’s not surprising that cases severe enough to land people in the ICU and on ventilators can involve long recoveries, one startling aspect of the virus is that even mild cases can drag on for quite some time. One study showed that more than a third of adults with mild cases—those not requiring hospitalization—had still not returned to their usual health two to three weeks after an initial positive test. For reference, more than 90 percent of outpatient influenza patients recover within that time period. Another study (in preprint) estimated that around one in seven symptomatic cases will last for at least four weeks, one in 20 will last for at least eight weeks, and about one in 45 will last for 12 weeks or more.

These long haulers, many of whom appear to be young and otherwise healthy and some of whom are children, continue to experience a range symptoms that can include debilitating fatigue, shortness of breath, cough, headaches, brain fog, gastrointestinal distress, and cardiac irregularities, including POTS. One study found that nearly 20 percent of COVID-19 patients were diagnosed with mental disorders, including anxiety, depression, or insomnia, within three months of their illness.

Another study followed more than 1600 patients with severe COVID-19 who had been hospitalized. The authors found that of the 75 percent of patients who had initially survived and been discharged from the hospital, 7 percent died and 15 percent were re-hospitalized within two months of discharge.

The second camp of COVID-19 morbidities includes organ damage with unknown long-term consequences. Again, the virus has surprised us by inflicting organ damage not only in individuals with severe cases but also in those with asymptomatic and mild cases. For example, one study of recently recovered COVID-19 patients, two-thirds of whom had asymptomatic or mild cases, found that 78 percent of the patients had experienced cardiac involvement and 60 percent continued to exhibit myocardial (heart) inflammation two to three months after diagnosis. Brain, lung, and kidney damage from COVID-19 have also been documented. This growing evidence has many experts concerned that the health repercussions of the virus could persist long after we control its spread.

We can’t just look at hospitalizations and bed capacity either. We’ve also got to look at what it actually means for COVID-19 patients and everyone else when hospitals become overwhelmed. ICU bed capacity is often used to judge how much trouble a region is in, but the real limitation of ICU capacity is ICU-trained staff, not bed space. (Many rural hospitals don’t have ICUs or ICU specialists at all.) ICUs typically care for patients with a large range of needs and operate at 70 to 80 percent capacity to allow some flexibility in case of a short-term increase in patients or in the proportion of patients who require the highest levels of resources. But patients with severe COVID-19 are among the sickest in the ICU. They require about twice as much care and stay three times as long as the average ICU patient, which means they can quickly overwhelm staff capacity before the beds are full.

When ICUs become overwhelmed, they’re forced to pull in non-ICU staff to help cover the surplus of patients. We saw this all-hands-on-deck crisis care occurring in New York and Houston earlier this year. Now it’s happening in hospitals around the country. North Dakota hospitals are so short staffed, the governor recently announced that healthcare workers who test positive for COVID-19 but are asymptomatic can keep working. As crisis care increases during a pandemic, so can the mortality rate.

Moving hospital staff from other units into the ICU as cases surge also impacts the care of non-COVID-19 patients. As we saw in March and April and are beginning to see again, hospitals are forced to halt elective procedures when overwhelmed. While it doesn’t sound like a big deal to stop performing nose jobs and facelifts for a while, people often don’t realize that many procedures that can be quite urgent—but not technically emergent—are also considered elective: cancer surgeries, joint replacements, cardiac ablations to correct rhythm problems.

The delay of urgent procedures—both because hospitals don’t have the capacity to offer them and because fewer people than usual are seeking care for serious conditions that require medical attention, such as heart attacks—can result in poor health outcomes and avoidable deaths. Some of these cases are likely reflected in the 100,000 excess deaths the CDC has reported through early October in addition to the country’s official pandemic death toll of nearly 250,000 people.

We can’t just look at skyrocketing cases either. We have to look at how the circumstances in which people are becoming infected are changing too. During the early months of the pandemic, many cases were linked to long-term care settings, large crowds, and tightly packed indoor spaces, such as bars. Hot spots emerged, like in New York, where community transmission became widespread. But in other parts of the country, especially in rural regions, the chance of encountering the virus if you avoided crowded locations remained small.

We’ve seen a massive shift in transmission in recent weeks, however; most of the country is now considered a hot spot. Because the virus has become so ubiquitous, a lot of transmission is also now occurring in places previously thought to be a safer alternative to large crowds: small, in-home gatherings. In some counties in the Midwest, for example, you’re now very likely to encounter an infected individual in a gathering as small as 10 people and almost certain to encounter one in a gathering of 15 people, according to a model created by researchers at Georgia Tech.

Infections spread within immediate households too. One study showed that among people living together in a single household, the rate of secondary infection—that is, the chance of another person within the household becoming infected from the first detected case—was about 53 percent. Studies in other countries have placed the rate between 20 and 40 percent. That means it’s not a lost cause if a family member becomes ill. Immediately isolating the sick person in a separate bedroom and bathroom, masking, opening windows, running air filters, washing hands, and sanitizing surfaces can reduce the risk of secondary infections within the home. (The entire family also needs to stay home to prevent spreading the virus to those outside the household.)

Despite the fact that the basic COVID-19 statistics are growing grimmer by the day, we have reason to hope that next year will be brighter: early data indicate that both the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines may be around 95 percent effective. And we’re not helpless in steering our way out of the depths of the pandemic even before vaccine approval and widespread distribution. Digging a bit deeper than the ever-present death, hospitalization, and case numbers flashing across every screen can give us a broader picture of our personal health risks from COVID-19, as well as those of our loved ones. This knowledge can help us to make more informed choices to reduce risk as we negotiate daily living. By masking, distancing, washing hands, and interacting outdoors rather than indoors as much as possible, we can still avoid many preventable morbidities and deaths.

We've been having the wrong conversation about abortion. Let's change it.

Image designed using uterus graphic by @pikisuperstar

I was pandemically, politically, and existentially exhausted. And then Ruth Bader Ginsburg died.

My first thought upon hearing of her passing was this: Who will fight for women now?

The answer, of course, is that we will continue the fight for our daughters and ourselves. But to do so, we need to admit we’ve been having the wrong conversation about abortion, the single issue that many Americans use to determine their vote for candidates whose platforms and actions run antithetical to most of the voters’ own values and to reality itself.

Whether abortion is moral—something we’ll never agree on—has nothing to do with how to reduce the abortion rate. We have decades of global and domestic data that show us how to reduce abortions. I’ll get to that part in a minute, but first I’ll tell you what does not stop women from procuring abortions: making the procedure illegal or heavily restricting it.

I spent the summer doing research for a new writing project on scientific literacy, which led me to read extensively about these two things: all the ways our brains are terrible at thinking critically, and all the ways interest groups—political parties, industries, religious institutions, you name it—prey on these deficiencies to successfully manipulate us.

I began to understand that modern anti-abortion discourse in the U.S. is one of the most effective political manipulations in our lifetime, the consequences of which extend far beyond reproductive rights.

But I’m seeing a fissure among some evangelicals who have been shaken awake by the hypocrisy of the “pro-life” Trump administration. It cages children. It denies the mounting, life-threatening dangers of climate change. (Yes, there is scientific consensus that it’s happening and that we’re in trouble.) And it has, to date, squandered more than 208,000 lives to a pandemic it has vehemently denied, despite growing—and quite impressive—scientific evidence on how insidious the virus is and how to control it. These evangelicals have woken up to the fact that the GOP reeled them in with one simple lie: that making abortion illegal saves lives.

I see a window here for evidence-based conversations that focus not on whether abortion is moral but about how to actually reduce the abortion rate—a goal most of us share, regardless of our reasoning.

Thinking critically about how to actually reduce abortions

To be sure, restricting or abolishing the legal right to abortion has consequences. Decades of global evidence show that women seek abortions when they feel they need them regardless of legality; when abortion is illegal or heavily restricted, they just procure them at greater physical, financial, and legal risk to themselves and their families. For obvious reasons, illegality therefore puts a greater burden on low-income women. Heavy restrictions on abortion punish women for having sex, no doubt. But they do not stop abortion from happening. In fact, over the last 30 years, the proportion of unintended pregnancies that result in abortion has increased in countries where the procedure is illegal or heavily restricted compared to the rate in countries where it is broadly legal. The lowest rates of unintended pregnancy and abortion, and the lowest proportion of unintended pregnancies that end in abortion are found in high-income countries where abortion is broadly legal.

If you were actually interested in reducing the number of women who feel they need abortions—as most people who provide reproductive health services are—here is how you would think critically about where to channel your vote, your voice, and your money. The process would only take about five minutes.

First you would look up the reason for most abortions. You would find that unintended pregnancies account for the majority of them. Globally, about half of pregnancies are unintended, and about 60 percent of unintended pregnancies end in abortion. In the U.S. in 2011, around 45 percent of pregnancies were unintended, and around 42 percent of those ended in abortion. To reduce abortions, you would need to focus on reducing unintended, unwanted pregnancies. (It get much more complicated to reduce the chance of abortion once an unintended pregnancy exists. Women who choose to terminate unintended pregnancies typically cite several reasons for feeling they could not continue the pregnancy, but the most frequent factor given is socioeconomic concerns.)

Next you’d look up how to reduce unintended pregnancy. Does abstinence-only education keep women from getting pregnant? No. The methods that prevent unintended pregnancy are these: access to free or affordable contraception, and education on how to use contraception effectively. When women have access to contraception and know how to use it, the rate of unintended pregnancy takes a dive. In 2014, publicly funded contraceptive services helped women in the U.S. avoid an estimated two million unintended pregnancies, 700,000 of which would likely have ended in abortion. With an uptick in contraceptive use, the abortion rate in the U.S. has been falling since the early 1980s.

Now you might look up data on whether making abortion illegal or highly restricted reduces the abortion rate. You’d find that countries where abortion is illegal almost always have higher abortion rates than countries where it is legal. Women who feel they need abortions have always sought them. Making abortions illegal punishes women by making the procedure more dangerous in numerous ways, but it does not save fetuses.

If you were in the business of saving lives, you would then look into which political parties and organizations advocate for preventing unintended pregnancy by providing free or affordable contraception and comprehensive sex education. You would find that the Democratic Party and Planned Parenthood are among these organizations.

So, if making abortion illegal doesn’t prevent the procedure from happening, and Democratic policies and Planned Parenthood services actually reduce the abortion rate, why is the anti-abortion movement staunchly associated with the GOP? The answer is nothing short of sordid.

The Grand Manipulation of the Christian Right

Jesus never commanded Christians to legislate women’s bodies; that was a Republican strategist named Paul Weyrich, a Southern Baptist televangelist named Jerry Falwell, and some of their loud conservative buddies. The story is long and well-documented from a variety of angles, yet rarely recounted. (I’ll give you an abridged version, but you can read more about it here, here, and here.)

It’s difficult to imagine today, but prior to the late 1970s, abortion wasn’t considered a political issue, nor was it associated with a particular political party. Most people considered it a “Catholic issue.” For centuries, Catholics had condemned abortion, first for being sinful if used to cover up fornication or adultery. Over time, the church went through many iterations of justification for scorning abortion, eventually settling on the idea that a fetus had its own rights. By the time Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973, Catholic opposition to abortion was actually couched in a liberal social welfare movement more associated with the Democratic Party. Liberal Catholics coined the phrase “right to life.”

But for the rest of the country, abortion just wasn’t very controversial. In fact, Southern Baptists, who fall into the broad category of evangelical Christians, affirmed during several conventions in the late 1960s and 1970s that abortion was acceptable under some circumstances. Other evangelical churches and Christian publications, including Christianity Today, did the same.

Immediately following Roe, the Virginia Baptist Convention’s Religious Herald wrote: “Religious liberty, human equality and justice are advanced by the Supreme Court abortion decision.” They wanted nothing to do with the liberal Catholic right-to-life argument.

Also in response to Roe, well-known evangelist W. A. Criswell, a former president of the Southern Baptist Convention wrote: “I have always felt that it was only after a child was born and had a life separate from its mother that it became an individual person, and it has always, therefore, seemed to me that what is best for the mother and for the future should be allowed.”

Evangelicals were not politically active as a group at the time, though many Southern Baptists had been Democrats since the end of WWII.

By the 1970s, the GOP was struggling, and it needed to drum up a reliable bloc of new voters if it were going to hold on. A conservative Republican strategist named Paul Weyrich noticed something as he began to think about whom to target: Southern Baptists were growing disenchanted with the Democrats over several issues, including taxes.

Religious historian Randall Balmer pieced together what followed from the personal papers of Paul Weyrich and Jerry Falwell. Falwell abhorred the Civil Rights movement. (Falwell is not to be confused with his son, Jerry Falwell, Jr., who urged evangelical support of Trump, was recently ousted as president of Liberty University following an alleged sex scandal, and whose dealings as president are now being investigated by the university.)

In protest of school desegregation in the 1960s, as became a trend with Southern Baptists, Falwell created a “segregation academy”—a private, Christian school for whites only called Lynchburg Christian School. After a legal battle related to the tax status of segregation academies, Republican Richard Nixon demanded that the IRS not grant tax exempt status to these schools because their racial discrimination violated the rules of what constitutes a charitable organization. Falwell and his fellow Southern Baptists were enraged by this development.

Weyrich noticed that racial discrimination surrounding the segregation academies had become a rallying cry among Southern Baptists and thought Republicans could capitalize on their fervor to politicize the group. (Never mind that it was actually a Republican president who created the policy; Weyrich brushed this detail under the rug.) The problem was that it didn’t seem appropriate to add blatant racism as an official GOP platform to bring them on board. Weyrich had to find another issue to attract them that would be more palatable for the evangelical masses.

Simultaneously, the GOP was toying with trying to lure Catholics to the party by taking a rather moderate anti-abortion stance for the first time. It didn’t work the way they’d hoped, though. Despite the staunch teachings of the Catholic Church, Catholic voters turned out to be a mixed bag at the voting booth.

The concept, however, gave Weyrich an idea. He tested abortion on the riled-up Southern Baptists as a potential issue to unite them politically. Prior to Roe, many had viewed the Catholic Church’s anti-abortion stance as simply an extension of its anti-contraception stance, but in the years since, abortion had become more associated with the leftist feminist movement and the sexual revolution, and this association was starting to concern evangelicals. They began to view abortion as a symbol of the nation’s disintegrating morality.

This, Weyrich realized, was the winning issue. He reached out to Falwell and others with large evangelical platforms and convinced them to start an anti-abortion movement. The GOP would make a place for them and their conservative social agenda if they could fire-and-brimstone their followers into believing that their religion deemed abortion immoral, and that the GOP could stop abortion in the U.S. by overturning Roe. The partnership would be mutually beneficial, generating a larger Republican base and giving evangelicals a measure of political power.

Falwell took to the airwaves, mobilizing the Christian Right to condemn and politicize abortion, and declaring that the GOP could protect the unborn through legislation. He created the Moral Majority in 1979. Falwell and others proof-texted the modern “pro-life” movement right into their religion and convinced followers that it was the issue they should prioritize above all others at the voting booth.

(Falwell later founded Liberty University, where alumni have reported convocations three times per week that often focused on political indoctrination. In response to the Sept. 11 attacks, he infamously said: “I really believe that the pagans and the abortionists and the feminists and the gays and the lesbians who are actively trying to make that an alternative lifestyle, the ACLU, People for the American Way, all of them who try to secularize America…I point the finger in their face and say you helped this happen.”)

In the late 1970s, evangelical theologian Francis Schaeffer egged on this new anti-abortion agenda, offering evangelicals graphic films and fresh vocabulary—infanticide and eugenics—to equate with the procedure.

The strategy worked; evangelical voters obliged and have since proved to be a shockingly homogenous voting bloc. In fact, 81 percent of white evangelicals voted for Trump in 2016, and they continue to comprise a healthy chunk of his base.

The marriage between the GOP and the modern anti-abortion movement relies on a culture that denies evidence-based reasoning—after all, only by denying evidence could you maintain your essential position that making abortion illegal stops it from happening. This culture now spans far past reproductive rights. It has transformed into one of intense science denial, which has resulted in the deadly denial of climate change and of the existence and severity of the COVID-19 pandemic, among many other issues.

So where does this leave us?

The GOP’s manipulation surrounding the politicization of abortion has left us with blocs of single-issue voters, many of whom do not understand that the “pro-life” cause does not save lives, how abortions are actually prevented, and how the movement was crafted specifically to take advantage of their political support.

We know how to reduce abortions, and it is a far cry from the GOP’s silver bullet that amounts only to legislating women’s bodies. Preventing unintended pregnancies requires supporting free and affordable contraception and comprehensive sex education. It also requires men to stop ejaculating irresponsibly, in the words of Gabrielle Blair, and raping women. Offering more women what they need to consider continuing unintended pregnancies requires supporting access to affordable health care for all, paid maternity leave, paid sick leave, equal pay for women, affordable childcare, and strong public education. It requires dismantling systemic racism, too. Let’s challenge ourselves to change the conversation.

Support your local book shop

Great news! Distribution for Equus Rising has expanded, which means you can purchase it just about anywhere books are sold.

If you’d like to stay home, you can now support your local book shop by buying copies through these websites:

Many indie stores are also offering curbside pick-up. Just call ahead and ask them to order the book for you.

If you enjoy the Equus Rising, please consider leaving a brief, written and starred review on Goodreads and the website where you purchased the book. Reviews greatly help the book’s visibility for future readers. Thank you!

Podcast interview with The Luminous Mind

I'm happy to share that my interview with Rebecca Bohman of The Luminous Mind Podcast is now available for your listening pleasure.

In the interview, we covered a full range of topics relating to lifelong learning, including my impetus for writing Equus Rising. I'm hopeful that our discussion of the importance of broadening our narrow perspectives on history will resonate with even more people today than it would have when we recorded the conversation on May 7.

We also talked about how my approach to homeschooling has evolved over the last three years, as well as the benefits I see in teaching kids photography. (More minds might be open to these discussions as of mid-March, too.)

You can listen to the podcast here:

The Luminous Mind Podcast website

Libsyn (iTunes and Stitcher Publisher)

YouTube

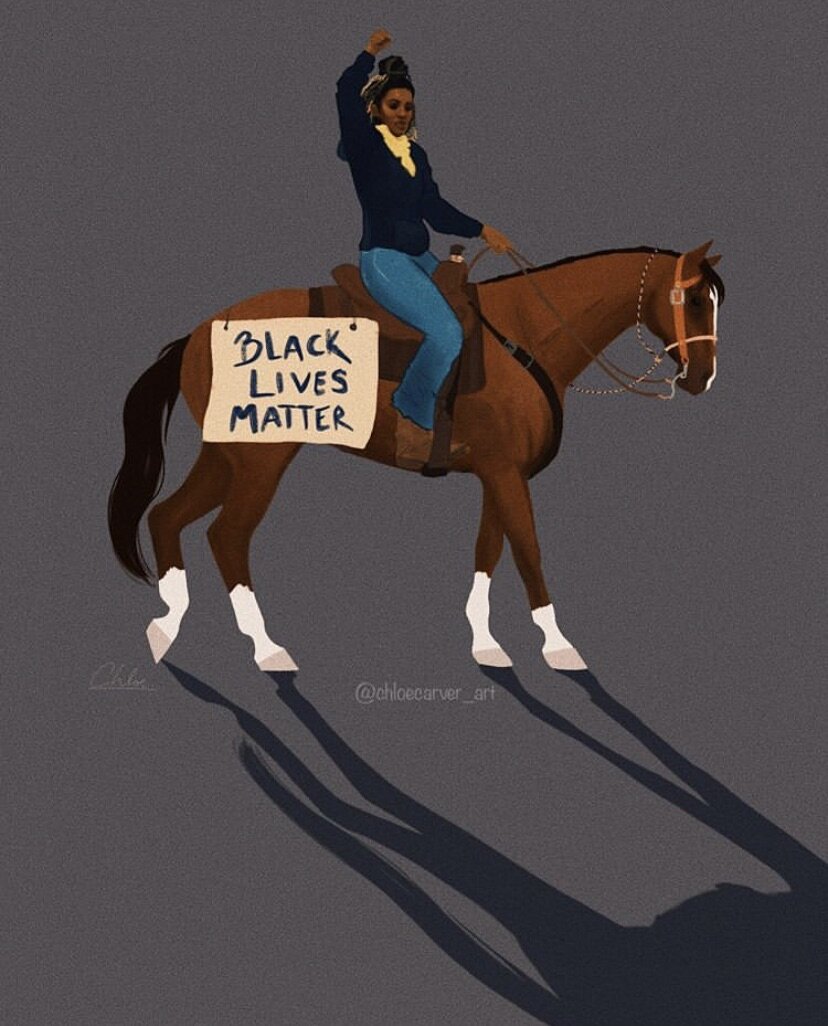

Our country has long excluded people of color from accessing the power of the horse

Art by Tess Whitfort. (Used with permission)

The image was striking: a young black woman riding an enormous horse through the Oakland protests, fist raised above her head. It was bold, powerful—and uncommon, as the equestrian world is heavily white.

“There has to be a change in horse sports. This cannot be so white,” Brianna Noble, the protester in the image, told Heels Down magazine. “As a black person who rides, I experience some of the blatantly racist stuff and then I get those who just won’t acknowledge me, won’t look me in the eye. And I’m an adult. There are kids out there who stop riding because of racial pressure and the hostile environment it causes. Race is this awkward thing that people don’t really talk about. And the silence is stifling.” (See the photo and read the article here.)

Equine sports are exorbitantly expensive. So it would be easy to explain away racial disparities as a simple matter of financial barriers. If people of color in this country have less wealth than white people, of course it follows that fewer people of color can afford to participate in a costly industry—one that, by the way, is not just about entertainment but includes activities that build confidence, work ethic, and responsibility; and offers therapies for numerous physical and mental health issues. The economic disparity is problematic, but surely no one is against the involvement of people of color if they can afford it, right?

I’m not a person of color and am quite open about the fact that my knowledge of horses is on the intellectual/historical side rather than on the practical side. I’m not the right person to speak with authority on the ways in which racism manifests in the horse industry today. There are many other people, including Brianna Noble, who have much to say on that subject.

But having spent the last few years studying and writing about how the horse shaped U.S. history, I can tell you with certainty: you can’t follow the thread of the horse without encountering the history of systemic racism surrounding it. Today’s barriers to the horse industry extend far beyond cost alone.

Art by Maria Elena Serratos. (Used with permission)

The story line of much of our country’s early development is simple: whoever wielded the horse most effectively won, whether victory meant land, money, status, or all three. First, the Spanish reintroduced the horse as a weapon to conquer the Americas. They recognized the horse’s power and clung tightly to it, initially banning the native peoples they encountered from riding. But the greatest source of Spanish strength became their own downfall when the native peoples of the Great Plains did access these horses—and learned to employ them much more effectively than the Spanish ever had.

This power shift arguably cost the Spanish North America. Maddeningly for the would-be colonizers, these Horse Nations managed to relentlessly beat back white encroachment into much of the plains for nearly 200 years.

And then. It was as if the whole country seemed to take note at the same moment that horses meant dominance. The attacks came from every angle on people of color who had gained power or status in some way through horses. In the late 1800s, the government realized it would only be able to remove the Horse Nations from the Great Plains—the last swath of uncontrolled U.S. soil at that time—by “relieving them” of the source of their incredible strength: their horses. Any excuse to “relieve” the horses from the indigenous people of the East was a good one, too. (The forced relocation process known as the Trail of Tears alone stripped these nations of thousands of their horses.)

Meanwhile, the racing industry began to erase the legacy of famed black jockeys from its history after segregationist laws essentially banned them from the sport in the early 1900s. (Some of these jockeys had survived enslavement prior to the Civil War and then risen to celebrity status in the industry.) And an emerging genre of literature, the western, wrote the one-fourth of cowboys who were black right out of the history of the West, portraying the scene as almost exclusively white.

In short, white Europeans first controlled access to the modern horse in what would become the U.S. As the horse became more ubiquitous, some people of color were able to draw power from it. However, through the forces just described, alongside other facets of systemic racism that have plagued the U.S., white Americans eventually reclaimed the horse quite forcefully for their own.

All that is to say, labeling the issue of racial disparities in the horse industry today as a matter of finances, while troubling enough, is a gross simplification that denies centuries of U.S. history.

Access to and mastery of horses no longer equates to dominance in the same ways it did a few hundred years ago. But that’s not an excuse to accept that people of color have a long history of exclusion from the benefits horses still offer. For one thing, in a $50-billion-per-year industry, there’s a lot of money to be made for those who rise to the top. Perhaps more importantly, horsemanship skills and horse-human relationships empower youth and adults by boosting confidence and teaching work ethic and responsibility. Many types of equine-assisted activities and therapies address physical and emotional issues, as well.

Brianna Noble is channeling the national attention she received from her protest ride on her horse, Dapper Dan, to follow her dream of launching a program for people historically excluded from accessing horses: “Humble, a project with the mission of exposing underprivileged and marginalized communities to the horse world, fosters respect, confidence, and accountability for urban youth through equine experiential learning.” I hope you’ll read about Humble and consider making a donation to help get the program off the ground.

The organizations below also seek to empower young people of color and at-risk communities by supporting them in learning horsemanship skills and participating in equine-assisted activities and therapies. I hope you’ll consider joining me in reading about their work, amplifying their messages, and, if possible, donating to their programs. And please send me more organizations to add to the list!

Ebony Horsewomen

Saddle Up and Read

Compton Jr. Equestrians

Urban Saddles

CBC Therapeutic Horseback Riding Academy

CORRAL Riding Academy

Sage to Saddle

Fletcher Street Urban Riding Club

Philadelphia Urban Riding Academy

And here’s a podcast of interest, too:

Young Black Equestrians Podcast

Art by Chloe Carver. (Used with permission.)

Art by Cristina Ibarra. (Used with permission)

Happy publication day + virtual book launch tonight

Happy Publication Day to Equus Rising: How the Horse Shaped U.S. History ! The book is now available on Amazon in paperback and Kindle editions. (The Kindle edition is a print replica format, so please make sure it's compatible with your device before purchasing.)

Let's celebrate together! Illustrator Robert Spannring and I would like to invite you to our virtual book launch party tonight, May 14, on Instagram Live at 8 p.m. EST. (Update: You can now view an abridged video of the launch here.) I'll be hosting the party on my account, @juliasoplop. To join, open the IG app, go to my profile at that time, and click on my profile picture, which should bring up the live feed.

At the launch, we'll answer questions about why and how we wrote and illustrated the book, do a very short reading, and give away a paperback copy. To enter the giveaway, all you have to do is submit a comment or question during the live event. We'll announce the winner at the end. I can't wait to get this book into your hands!

Hope to see you tonight.

The complex interplay between human epidemics and climate isn’t new

People in the U.S. who live in areas with high levels of air pollution are more likely to die of COVID-19 than people who live in areas with lower levels of air pollution, according to the pre-print of a new study by Harvard researchers. The study examined long-term exposure to air pollution. A separate European study also links air pollution to higher COVID-19 mortality rates. In other words, the virus is significantly more deadly in areas where humans have substantially degraded air quality than in areas where humans have degraded air quality less.

On the flip side, reports from around the world are showing one positive consequence of the pandemic: reduced levels of air pollution. Lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, and fear have kept much of the global population out of cars and off planes in recent months. The burning of coal has decreased. Factory production is down. From China to Italy to the U.S., levels of carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen dioxide have fallen since COVID-19 emerged.

While these reductions offer interesting and unusual data sets, they’re likely temporary and won’t have much of an influence on climate change or on the long-term health of residents in more polluted places. Areas of China that were hard hit by the virus, for example, and are now reopening are already seeing emissions creeping back up.

But this is not the first time in history that human epidemics have influenced the environment or the climate. While researching my book, Equus Rising: How the Horse Shaped U.S. History (May 14), I came across a fascinating study published last year in Quaternary Science Reviews, which showed that after Europeans arrived in the Americas in 1492, they wiped out so many indigenous people so quickly through a combination of warfare, resulting famine, enslavement, and disease—though primarily through disease—that they contributed to a change in the global climate. Within a century of European arrival, the study estimates the Americas had been depopulated by 90 percent. That’s 55 million deaths—about 10 percent of the global population at that time.

The event, referred to as The Great Dying of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas, was largely the result of not just one but numerous epidemics: smallpox, measles, influenza, and the bubonic plague, followed by malaria, diphtheria, typhus, and cholera. Many of these peoples lived in large, agricultural societies. When they died, they abandoned their cultivated lands, which quickly reforested. The massive number of new trees began to suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, lowering global temperatures to a degree that could not be accounted for only by other natural processes, and ushering in the Little Ice Age of the 1600s.

Every early reviewer of my book wrote a note in the margin next the description of the event that said something to the effect of: “Wait, what??? I’ve never heard of this!”

Their comments probably stemmed from the fact that the Industrial Revolution is largely cited as the beginning of human activity that has significantly contributed to climate change. But this study suggests human epidemics were impacting the climate at least 400 to 500 years ago.

A complex interplay exists between human epidemics, the environment, and the climate. In the last few months, we’ve seen that people who live in areas with more air pollution die from COVID-19 at higher rates than people who live in areas with lower air pollution. We’ve also seen that people’s reduced movements during the pandemic have led to reduced air pollution in the short term. But can we expect long-term environmental and climate consequences from this pandemic?

Perhaps. The heavy economic fallout from COVID-19 will likely spur countries to create more stimulus packages to jump start their economies. If these packages include substantial funding to reduce carbon emissions and mitigate other climate risks, as many climate advocates are calling for, we could experience another human epidemic influencing the climate in a significant way.

My interview on Feathered Quill

This post is short and sweet. My author interview with Feathered Quill is live, and you can read it here. I discuss my impetus for writing Equus Rising, what my research entailed, and challenges I encountered along the way. I also give some blunt advice for aspiring writers.

How my book research revealed a personal connection to the wild horses of the Outer Banks

When you start to dig, you never know what you’ll find. In researching the origins of the wild horses of the Outer Banks of North Carolina for my book, Equus Rising: How the Horse Shaped U.S. History (May 14), I found something, as a Minnesota native, I could hardly believe—a historic personal connection to them.

Legend has it the small, hardy Spanish horses of the Outer Banks swam ashore from sinking Spanish ships in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. This region is the Graveyard of the Atlantic, after all. It’s littered with more than a thousand shipwrecks, and some of those ships carried horses and lost them to storms. It’s a romantic story, but we don’t have evidence to confirm that any horses survived these wrecks, swam ashore, and procreated.

What we do know is that by the 1650s, European settlers started to move into the North Carolina mainland west of the Outer Banks and north of the Albemarle Sound. This area attracted a unique population mix: formerly enslaved peoples, runaways from the law, Native Americans, and Quakers escaping persecution in Virginia. These settlers were mostly small-time farmers. Many owned horses. In the second half of the 1600s, some of them began to use the Outer Banks as pasture to avoid the need for fencing and the tax England began to impose on fencing in 1670. Eventually, these settlers abandoned many of the horses to the wilds of the barrier island.

As I absorbed this information, I realized the description of this interesting community of people near the Albemarle Sound was vaguely familiar. When I got to the word “Quakers,” my brain lit up. I ran to my living room bookshelf and pulled off a book my great aunt wrote about my colonial Quaker ancestors, the Hill family. Sure enough, they were among the first European settlers in the Albemarle region.

I don’t know whether they had horses or whether they pastured them on the Outer Banks, but it’s possible they put some of the first horses there. Certainly their community did. I doubt we’ll ever know one way or another, but this idea alone made me grow even fonder of these horses and their place in history. I look forward to sharing more about the wild horses of our eastern barrier islands with you in Equus Rising when it’s released on May 14 on Amazon.

You can download a free sample chapter of Equus Rising by clicking here and scrolling to the form at the bottom of that page.

Meet the illustrator of “Equus Rising”

As our May 14 publication date for Equus Rising: How the Horse Shaped U.S. History approaches, I’ll be sharing details about the book each week.

Today I’m delighted to introduce you to the illustrator, Robert Spannring. I’ve been a fan of Robert’s art for years, and as soon as the first chapters of this book began to take shape, I started to think about how his pen and wash style could bring the history to life. I couldn’t believe my luck when he signed on to the project. When you see the nineteen illustrations he contributed, which are more unique and imaginative than I ever could have envisioned, you’ll understand why.

Below you can read Robert’s extensive bio. You can also visit his website to view and purchase his work, including some of the original drawings that appear in the book. You can also find Robert here:

Instagram: @spannringfineart

Facebook: Robert Spannring

robert@robertspannring.com

Robert Spannring has been a professional painter and illustrator for fifty years. Born and raised in Livingston, Montana, he grew up sneaking away from school to draw the landscape and its wildlife and explore what might be around the next corner. He began his career as an illustrator and watercolorist.

He was the Artist-In-Residence at the Lake Hotel in Yellowstone National Park, where his work is exhibited throughout the hotel. He also worked with Jack Horner at the Museum of the Rockies, providing the interpretive dinosaur illustrations for the Special Museum Exhibits.

Spannring has done illustration work for the Greater Yellowstone Coalition (of which he is a founding member), Orvis, Winston Rods, Defenders of Wildlife, the U.S. Forest Service, the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks, the Boone and Crockett Club, Montana Audubon Council, Roberts Reinhart Publishers, and Sasquatch Books, among others.

Spannring added oil and plein air painting to his artistic repertoire and is now a member of the distinguished Montana Painters Alliance, the Impressionist Society, and the Oil Painters of America. His work has been selected for exhibits and auctions by the Charles M. Russell Museum, the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, the Yellowstone Art Museum, the Missoula Art Museum, the Paris Gibson Square Museum of Art, the Hockaday Museum of Art, the WaterWorks Art Museum, and galleries throughout the West. Spannring’s work is also in private collections throughout the U.S.

Why the Great Epizootic of 1872 should give us hope for change after COVID-19

The virus swept through nearly every major city in the U.S. and Canada over the course of a year. It killed 1-2 percent of its victims and kept the rest out of work for weeks. Cities grew chaotic. Public transportation ceased to operate. Food shortages and price gouging ensued. Economies ground to a halt.

Sound eerily familiar? There’s a major difference between this event, the Great Epizootic of 1872-1873, and the one we’re experiencing today, however; the Great Epizootic infected horses, not humans.

Throughout most of the 19th century, the horse served as a primary energy source in the U.S. Horses hauled goods, transported people, powered agricultural work, and fueled the Industrial Revolution. In this era before widespread electricity and automobiles, they were essential to business and everyday life.

The Great Epizootic alarmed the human population of the U.S. It wasn’t the first horse disease outbreak to spread through the country—for example, glanders, an extremely contagious and deadly disease, infected 11,000 military horses during the Civil War—but its consequences were far-reaching and impossible to ignore.

As I’ve been making final edits to my book, Equus Rising: How the Horse Shaped U.S. History (May 2020), in which I discuss the Great Epizootic, I’ve been finding myself drawing parallels between that event and today’s COVID-19 pandemic.

The Great Epizootic, along with other horse epidemics of the last half of the 1800s, spurred structural changes. For starters, formal, accredited veterinary schools began to crop up in the U.S. with the main objective of caring for the horse as a means of protecting the economy. (Yes, providing compassionate care to your sweet family pet was an afterthought.)

Second, having experienced them first hand, people began to understand the economic dangers of complete reliance on an animal that could get sick and taken out of the workforce. To reduce the risk of a Great Epizootic replay, the U.S. needed to find alternative forms of energy. Horse epidemics helped to catalyze the development and adoption of these new energy sources.

The fact that horse epidemics drove societal change is relevant today. Sure, we’re dealing with a human pandemic, but we’re witnessing many of the same consequences horse pandemics caused 150 years ago, including personal and economic disruptions. The resulting shifts following those epidemics give us hope for sweeping improvements in the societal failings COVID-19 has and will starkly reveal.

For as long as I can remember, epidemiologists have been warning us that a pandemic was a “when” not “if” scenario and that our country was woefully unprepared for it. In fact, just five months ago, a draft report evaluating the government’s pandemic preparedness determined our ability to coordinate a response to a pandemic is abysmal. (This report just became public.)

We are unprepared—not because the idea of a pandemic should surprise anyone, but because we often ignore threats that haven’t been a part of our personal experiences. We can think of them as simply hypothetical instead of looming if we haven’t lived through them ourselves.

I’m hopeful that after witnessing firsthand how broken or inadequate so many of our systems are, those of us who come out the other side of this pandemic—and that’s most of us—will demand extensive improvements across numerous sectors. None of us has an excuse to shy away; now, whether we previously understood these problems or not, we’re experiencing them personally. In our businesses. In our homes. In our bank accounts. Below are some of the areas in which I see potential for improvements following the pandemic.

Government: Pandemic/disaster preparedness and leadership

Whether we’ve ever been ready for a pandemic, recent missteps by the Trump administration likely increased our vulnerability: dismantling the National Security Council pandemic team in 2018 (here is a piece from someone who had previously led that team about the role they would have played in handling our response to COVID-19); largely ignoring a draft report released five months ago following a pandemic simulation that declared the U.S. was vastly underprepared to handle a pandemic; canceling the global PREDICT program that same month, which sought to identify, track, and research emerging zoonotic diseases; and initially denying the pandemic was a threat to the U.S when evidence showed we needed to be aggressively working to contain it.

And what happened at the CDC? Who made the deadly decision not to use the WHO test kits or to appropriately scale-up the manufacturing and distribution of our own, rendering us unable to identity, track, and contain cases?

The government can no longer find excuses to brush our pandemic/disaster unpreparedness under the rug and redirect funding away from it. We’re all experiencing the consequences of denial and inadequate preparation. Now is the time for us to demand accountability in this area at every level of government.

U.S Health Care “System” / Lack of U.S. Health Care “System”

We don’t actually have one “health care system” in the U.S. We have numerous dislocated systems, many of which are underfunded and inaccessible to many Americans. Despite increases in coverage due to the Affordable Care Act, 27.5 million people in the U.S. did not have health insurance for the entire year in 2018. Health care costs have skyrocketed, even for those with coverage. This study showed the U.S. spends about twice as much on health care as 10 other high-income countries do, but has the lowest life expectancy and the highest infant mortality rate among them. Globally, the U.S. ranks 43rd in life expectancy at birth.

The cracks in our ability to provide adequate health care to all Americans will show up—and already have been—in bas-relief as we analyze the consequences of the pandemic here and compare them to the results in countries with some type of universal health coverage and a willingness to introduce more aggressive public health measures. (South Korea’s management of the crisis has been astoundingly different from our own, for example.) We know our “health care system” lags behind many other countries’, but data may soon provide an even blunter picture that might convince more people it’s time to change our ways.

Emergency Preparedness

Why have hospital administrators not stockpiled masks, gowns, gloves, and ventilators, when they’ve always known a pandemic was imminent? It’s unfathomable, and I don’t have answers for you. (I’m not sure how much of this preparation should fall to the government versus hospitals, but I’m not impressed with the preparedness strategies of either right now.) No medical professional should be forced to confront a pandemic with a homemade mask. I hope the administers at every hospital are reprioritizing future spending right now to adequately protect their staffs.

Telemedicine

Telemedicine is a growing industry, and about half of U.S. hospitals already use some form of it. During this pandemic, many providers have suspended most or all in-office appointments and are providing telemedicine instead. Analyzing the results of this larger-scale deployment of telemedicine could help us to better understand in which conditions it provides the most efficient and effective way to deliver care and improve accessibility.

Anti-Vaxxers

Anti-vaxxers benefit from the protection of herd immunity—large numbers of people who have been vaccinated or have already been exposed to a disease. But now they’re personally experiencing what happens when a disease spreads in the absence of a protective herd. It’s scary. It’s disruptive. It’s deadly. And it demonstrates what a world without vaccines did look like until relatively recently and would look like again if we reverted back to one. Might this experience shift some views?

Education

I’ve read numerous estimates that those of us with young kids should plan to save several hundred thousand dollars per child to send them to in-state universities. (Here’s one calculator.) For most of us, that number is laughably out of the question. We’ve got to find alternative ways to provide higher education to our children, or it’s just not going to happen.

Distance learning has, of course, been expanding for years, but some universities are hesitant to move their instruction online and make it more financially accessible to greater numbers of people. Now the pandemic is forcing them to teach online. I hope this move to virtual instruction will continue to demonstrate that online education is feasible and legitimate when done well.

Business

About one-quarter of civilian workers in the U.S. don’t have access to any type of sick leave. Perhaps the pandemic has shown companies that if they don’t allow and encourage employees to stay home when sick, they could go to work and spread a plague that could have disastrous implications for the company’s financial future. Society, and the companies within it, benefit when sick people stay home. Will the pandemic serve as a wakeup call for companies that don’t provide sick leave?

Small businesses are already struggling and shutting down after just a week or two without in-person customers. I hope this required “opportunity” to quickly spin up alternative revenue streams or ways to sell their products makes many of these businesses less vulnerable to future disruption.

Climate

We’re already seeing preliminary data that forced lockdowns, and even the encouragement to “shelter in place,” has temporarily reduced dangerous emissions around the world. (You can find some interesting related articles here, here, and here.) More data on this subject will emerge in coming months. I hope climate scientists will run with it both as a means to demonstrate that our collective actions can reduce emissions and to develop creative solutions for reducing emissions in the future.

There is hope yet

The Great Epizootic is just one example of how epidemics have catalyzed significant societal changes. When I begin to feel crushed by pandemic-induced anxiety, I try to refocus my energy towards what comes next. COVID-19, despite the devastation it’s causing across the globe, presents an opportunity to push for improvement. I’m hopeful we can use the momentum that comes from people finally understanding our vulnerabilities on a more personal level to demand structural transformation.

Sources for information on the Great Epizootic and glanders outbreak:

Kheraj, Sean, “The Great Epizootic of 1872–73: Networks of Animal Disease in North American Urban Environments,” Environmental History, 23, 3 (July 2018): 495–52.

Greene, Ann Norton. Horses at Work: Harnessing Power in Industrial America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008).

Becoming a more responsible consumer of health and science news in the age of COVID-19 (and always)

There’s nothing funny about COVID-19. But it’s a little funny that in any crisis, we suddenly think we’ve become relevant experts based on our few-days-worth of news consumption. As a hurricane approaches, we become meteorologists. The wind speed just shifted over the threshold. Now it’s a Cat 5! When an earthquake rattles us, we become seismologists. There’s a 10 percent chance that was just the foreshock, people! And now we’re finding that in the midst of a pandemic, we’re quickly becoming epidemiologists and infectious diseases experts. Who needs a PhD or MD and tons of experience researching and modeling disease spread to figure out what’s going on? Not me!

In crisis situations, many of us tend to suffer from a touch—or full-blown case—of the Dunning-Kruger effect, meaning we overestimate our competence. Many people also overestimate the competence of low-quality information sources that call themselves “news” but don’t report from an evidence-based perspective.

They’re overblowing it. (Said no legitimate epidemiologist on the planet.) It’s the same as the flu. (Said no one who understands the function of a decimal point or how to read a number off a piece of paper.) If I just stay six feet away from other people, there’s no way I can get the virus. (Said no one who understands how little we know about a virus that has been infecting humans for maybe three months and on which we have very little data.)

We can’t afford to go Dunning-Kruger on COVID-19.

So please. I beg of you. Be responsible consumers of health and science news. Don’t overestimate your competence. And understand that guidelines are continuously changing as more data emerges.

I’ve been out of the science writing game for a while, but my professional training is in medical journalism. (I’m not a medical professional or health sciences researcher.) I’d like to share some things with you that I’ve learned along the way about finding the most reliable sources of health-related information.

GO DIRECTLY TO THE SOURCE

If you’re wondering how we can still know so little about COVID-19 and why guidelines are rapidly changing, let me put the virus’ novelty in perspective. My daughter is allergic to peanuts. A few years ago, she participated in an oral immunotherapy clinical study to desensitize her to peanuts, meaning she started to eat miniscule bits of peanuts each day, then built up that amount over time to be able to tolerate some peanut exposure without reacting to it. The principle investigator of her study pioneered the field of immunotherapy for peanut allergies, beginning about 10-15 years ago. This field of study is still considered young. Just about every time I asked my daughter’s study team a question about her reactions or the long-term impacts of daily exposure to something she’s deathly allergic to, the answer was, “We don’t know,” or “We’re not sure yet.”

COVID-19 has been active in humans for maybe three months. We can expect a lot of “We don’t knows” and “We’re not sure yets” in the coming months from the most respected researchers out there. The patients in China are the first study subjects. The patients in Italy are the first study subjects. Some of us will become the first study subjects.

So how are public officials developing guidelines to help slow the spread of COVID-19 with limited information?